The re-election of Donald Trump challenges us to understand why authoritarian leadership has become more popular – especially in developed countries with long democratic traditions. By deepening our insight into why this trend is growing, we gain deeper clarity about what we can do to shift it.

The following systems framework helps us develop this understanding. More specifically, it shows how increases in wealth inequality, identity-driven politics, climate change, and authoritarian leadership are not only inter-connected but also feed on each other. Recognizing these dynamics helps us reshape them. The post concludes with what we can do individually and collectively to reverse these trends.

The Growth of Wealth Inequality

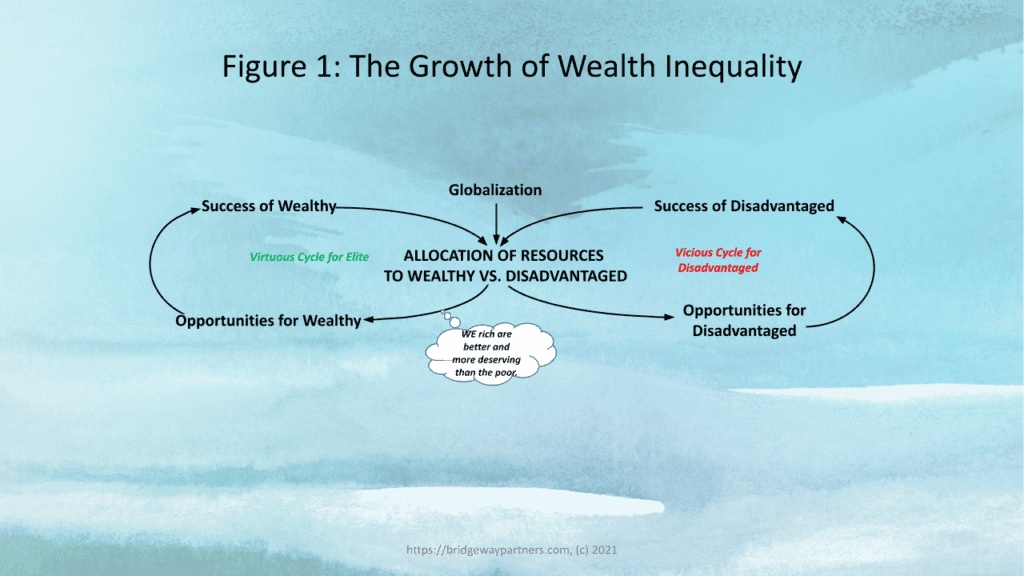

We start with a dynamic that is very common in all societies, not just capitalist ones. It’s called “Success to the Successful”, i.e. the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. One of the catalysts of this dynamic over the past four decades has been globalization. Globalization has enabled people at the top of the pyramid, not just in the US but also in other countries around the world, to benefit from an expanding economic pie. However, that pie is not being equally distributed. The elites in various countries around the world benefit enormously from globalization. Other people are left scrambling to keep their heads above water as costs are driven lower and lower. This dynamic especially hurts manufacturing workers and others in developed nations who depend on jobs that can be readily exported to lower-cost countries.

The elites benefit over time from a feedback relationship described on the left side of Figure 1 below. People who start off with more resources get more opportunities. They are more successful because of these opportunities. They then use their success to get even more resources for themselves. On the other side of the coin, people who start off with fewer resources are less able to generate new opportunities. They are then less successful because they have fewer opportunities. As a result, they are less able to tap into more resources. The disadvantaged are caught in a vicious cycle while the elites benefit from a virtuous cycle.

Many elites reinforce their virtuous cycle by assuming (as shown by the thought bubble on the diagram) that we are better and more deserving than those who are disadvantaged. People at the top often experience a sense of entitlement. There are also members of the elite who want to help the poor but fall into the trap of assuming they know what the poor need. Consequently, they mistake giving to the poor with empowering them.

Identity Politics and the Rise of Fear and Anger

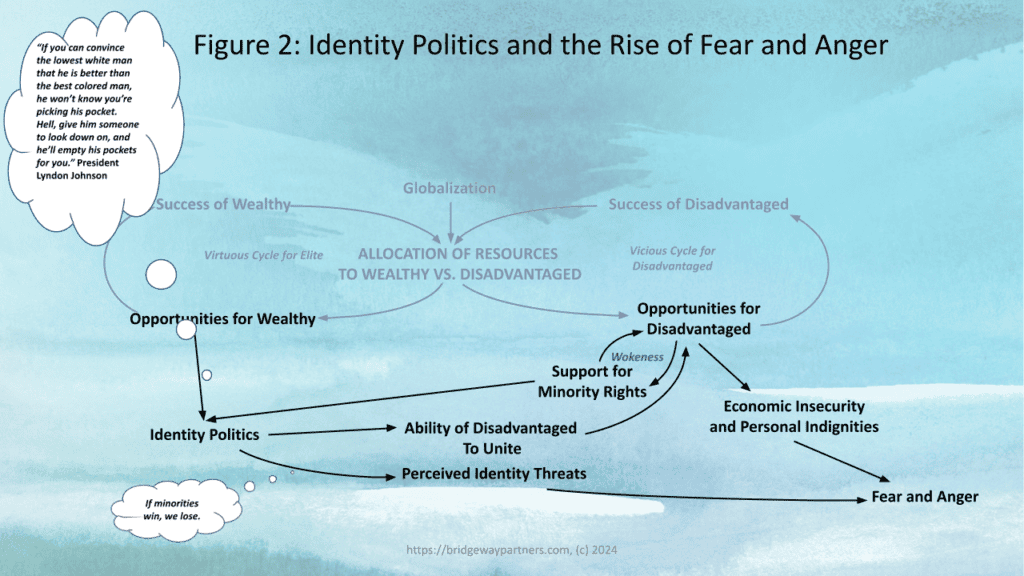

One way in which the wealthy retain power is through identity politics. They set poor people against each other on the basis of ethnicity or other identifiable differences. Trump used this strategy to divide less-educated white people from Americans of color. Sixty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson, an extremely astute politician, was asked why poor white people, typically Republicans, regularly voted against what seemed to be their economic self-interest. He responded, “If you can convince the lowest white man that he is better than the best colored man, he won’t know you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give them someone to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.” Trump has expanded identity politics to unite less-educated whites and Americans of color raised in the U.S. from recent immigrants and those trying to enter the country. One might also conclude that Democrats reinforced identity politics by both supporting minority rights through “woke culture” arguments and downplaying economic problems.

Disadvantaged people are less able to organize along economic lines because of identity politics. If the disadvantaged are unable to unite, their ability to strengthen their economic opportunities declines further. The wealthy are able to increase their opportunities proportionally. We can see this dynamic in the success of union-busting campaigns and weakening of the social safety net in the United States over the last 30-40 years.

People who are vulnerable to identity politics perceive that their identity, their very right to exist, is being threatened. The word “perceived” here is deliberate since it doesn’t necessarily mean that the threats are real. For example, a white person who feels threatened by people of color or by immigrants is not necessarily in economic danger. In fact, immigrant labor often creates new jobs for the dominant ethnic group. Whether the threat is real or perceived, people who believe their identity is being threatened feel afraid and angry. Beyond that, they feel greater fear and anger when they experience the economic insecurities and personal indignities that result from decreased opportunities. These dynamics are shown in Figure 2 below.

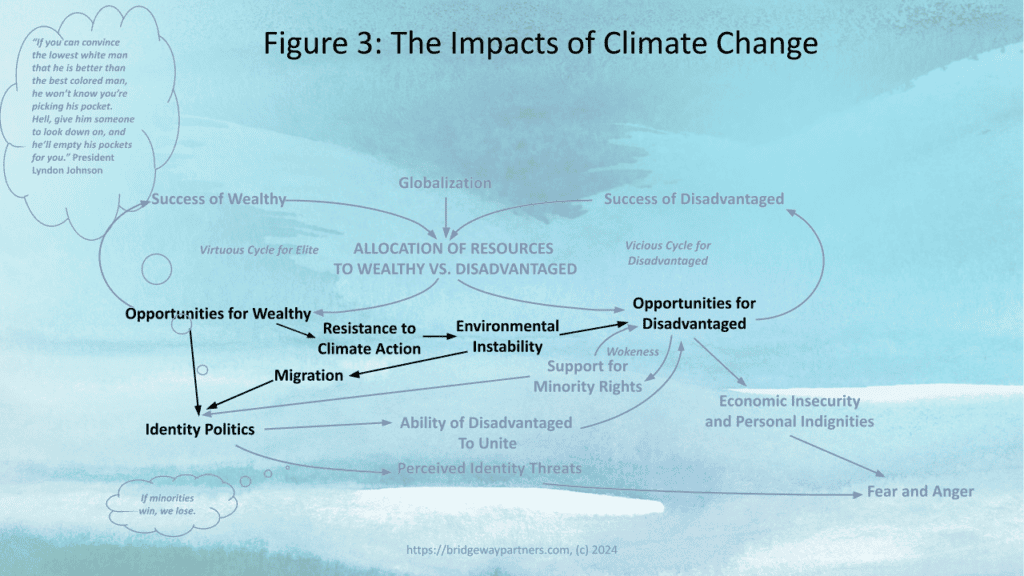

The Impacts of Climate Change

Wealthy people who benefit from the fossil fuel industry are more likely to resist climate action. The failure to aggressively address climate change increases environmental instabilities such as floods, droughts, wildfires, and intensified storms. These instabilities disproportionately hurt poor Americans in the short term. They also increase the vulnerability of poor people in nearby countries, further exacerbating migration pressures and the effectiveness of identity politics.

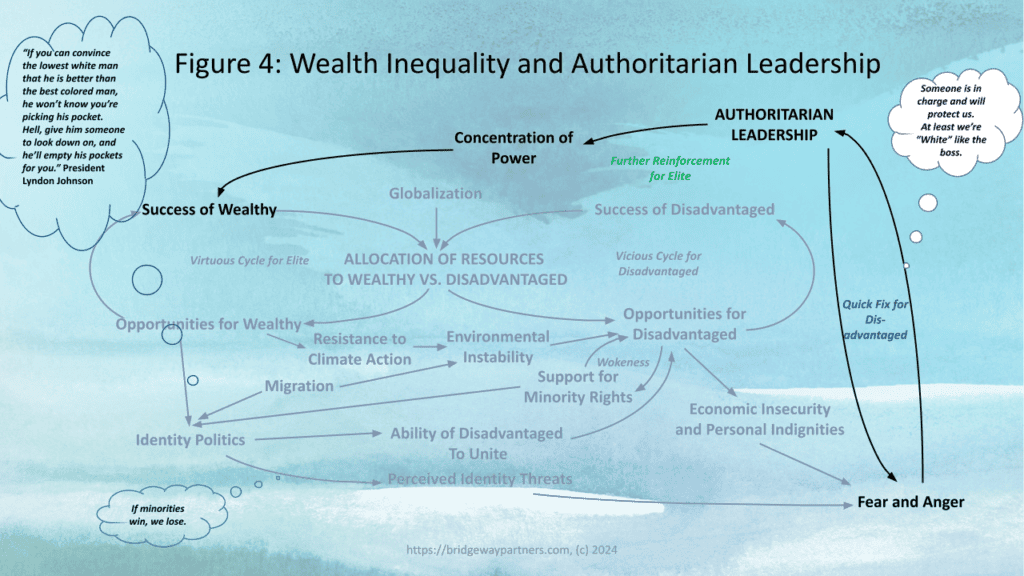

Authoritarian Leadership: A Fix That Backfires

Fear and anger lead to authoritarian leadership. Disadvantaged people, particularly from the dominant ethnic population, come to trust that someone is in charge, someone will protect them. The words used by participants at a 2020 Trump Presidential rally were, “He is our protector; he is our bodyguard”, followed this year by “Trump’s your daddy.” These are very powerful attributes to be granted by one set of adults to another adult. Authoritarian leadership works in the short term in that it enables disadvantaged people who experience identity threats, economic insecurity, and a loss of dignity to believe someone will value and take care of them.

However, over time, authoritarian leadership increases the concentration of power. And that concentration of power plays right into the hands of those wealthy people who believe they deserve everything they have and more. So authoritarian leadership ironically reinforces the strength of economic elites and leads to an even deeper vicious cycle for the disadvantaged. See Figure 4 below.

What We Can Do

In summary, wealth inequality, identity politics, climate change, and authoritarian leadership are mutually reinforcing factors that tend to increase over time. We can limit the growth of these factors by doing the following.

Individually, we can build bridges with people who are most marginalized by the current system. For example, we can join or support one or more of the following organizations. Braver Angels is “leading the nation’s largest cross-partisan, volunteer-led movement to bridge the partisan divide for the good of our democratic republic.” Living Room Conversations provides over 100 conversation guides that enable people across political, cultural, and economic divides to build mutual understanding and respect. DEPLOY/US is “a convener, regrantor, and accelerator of climate leadership across the political spectrum.” More in Common has teams in 7 developed countries including the U.S. whose mission “is to understand the forces driving us apart, find common ground and bring people together to tackle shared challenges.” Tangle is an “independent, non-partisan, subscriber-supported newsletter, read by over 150,000 people in 55+ countries … which summarizes the best arguments it can find from the right, left, and center on big debates in American politics.”

More broadly, we can work collectively to support political, business, and social sector leaders who are committed to:

- Redistributing resources rather than concentrating them further, e.g. through promoting more progressive taxation

- Generating new resources and distributing them more equitably, e.g. through investments in emerging industries and the small businesses that support them

- Focusing ethnically diverse poor people to take actions based on their economic commonalities, e.g. through strengthening labor’s influence on management decision-making

- Supporting religious institutions to reinforce ethical precepts that include compassion, tolerance, and respect for others

The results are that we will have not only a more equitable society, but also one that is more sustainable economically, socially, and politically.

Note: The original post is based on a panel presentation given by David Stroh at the 2020 International Leadership Association annual conference. It has been updated with new material presented at the November 2024 Next Practices Institute sponsored by Mobius Executive Leadership. The dynamics of wealth inequality are described in greater depth in David’s article in The Foundation Review, “Overcoming the Systemic Challenges of Wealth Inequality in the U.S.” Readers are also encouraged to read his blog post “How Wealth Inequality Compounds Racism” for further perspective.